Guest Blog - Richard Moore, The Cycling Podcast

Posted by Tom Copeland on

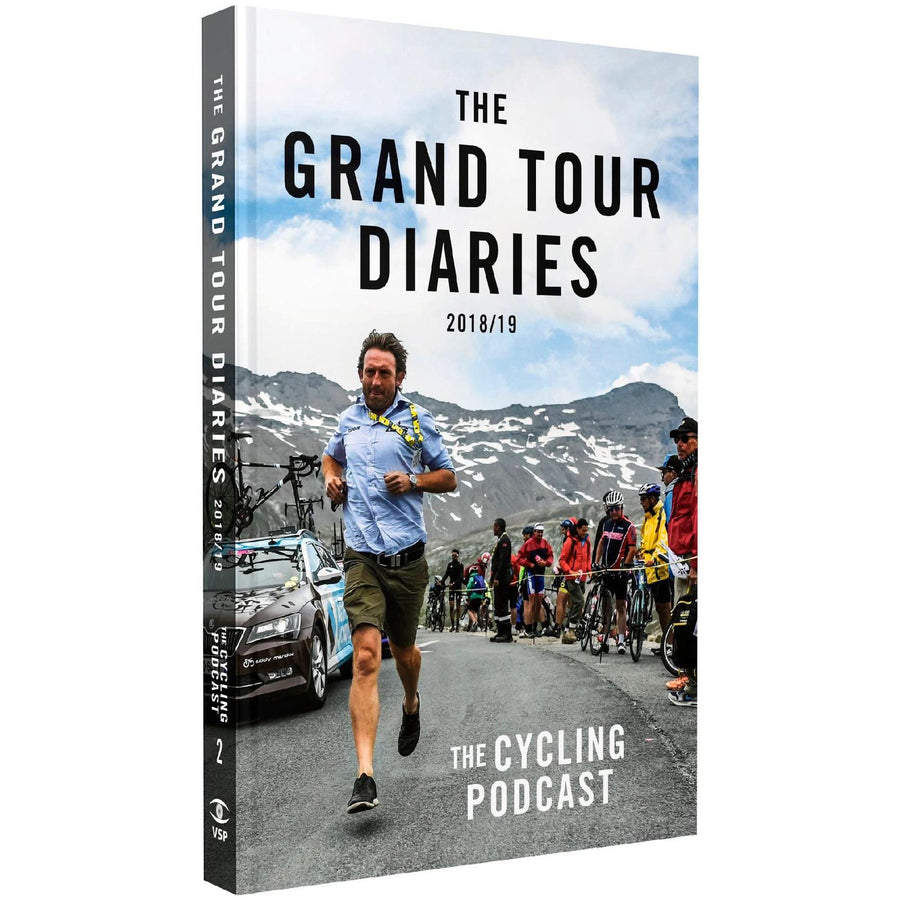

Richard Moore of The Cycling Podcast shares an extract from their latest book, The Grand Tour Diaries - one that lifts the curtain on their experience of covering the 2018 and 2019 editions of the Giro d’Italia, Tour de France, Vuelta a España and Women’s Tour. It was during the this summer's Tour and Vuelta that Richard and the team experienced the ATTO first hand, as he talks about here...

At the Tour de France and Vuelta a España we were fortunate to have the use of a folding bike. Not just any folding bike, but a sleek carbon fibre machine, the Austin Cycles ATTO. It was lightweight, easy to fold and pack in the boot of the car, but best of all, as far as I was concerned, it was oil-free.

I will never know how many awkward encounters I avoided by not having to make excuses for not shaking someone’s hand because of oily mitts. There’s a lot of hand-shaking at bike races. And, if you’re a journalist, there’s a lot of ground to cover on foot, from the car parks to the team buses to the press centres. Hence the value of a folding bike. It saved time. It saved my legs. It saved the rubber on the soles of my shoes.

It was also great fun. A bike, especially a folding bike, can take you places you wouldn’t otherwise go. From Foix, on stage 15 of the Tour de France, I ventured up the lower slopes of Prat d’Albis, the Pyrenean climb tackled for the first time by the Tour in 2019 – at least until it started raining, when I beat a hasty retreat to the team buses in the centre of the town.

At the Vuelta a month or so later we were confusingly nearby, just along the road in Pau (France), and I explored this lovely, understated city by bike. Pau is a place we visit every year on the Tour de France, but we never have time to look around because the Tour is so frantic and all consuming.

The Vuelta, by comparison, is affectionately known by some as the Holiday Grand Tour. In early September, on the day of the Vuelta’s time trial, I spent the morning riding along the Boulevard des Pyrénées, high above the Ousse river, ending up at the Château de Pau, the 14th-century castle that was Henry IV’s birthplace and which is now a museum. It’s a grand, dazzling place that should be swarming with tourists but isn’t, because this is Pau – weirdly unfashionable Pau – and the tourists are all in Biarritz, Bordeaux or, for different reasons, Lourdes.

A few days later, in another wonderful and underrated city, Bilbao, the bike came into its own as it carried me to a new climb, Alto de Arraiz. This was a few kilometres from the finish, it was actually within the city itself, but astonishingly, considering how many bike races are held in the cycling mad Basque Country, no race had used it before. Someone had written to Javier Guillén, the Vuelta director, suggesting the climb and when he went to see it, he ‘fell in love.’

When I got to the foot of it and saw how steep it was I did not fall in love – I got in the lift (another advantage of a folding bike) that carried me half-way up.

A day later came a climb that is a notorious classic of the modern Vuelta – Los Machucos. The following is an extract from The Cycling Podcast’s book, The Grand Tour Diaries, in which I describe my ride up Los Machucos:

Los Machucos is either spectacular or silly, depending on your point of view. The ramps at the bottom – slabs of slatted concrete at an almost impossible angle (the slats presumably to minimise the risk of tyres slipping) – are ridiculous. But it helps to give the Vuelta its distinctive identity and sets it apart from the Giro and the Tour, which probably wouldn’t risk such an extreme climb.

Climbs like this create problems for those of us trying to cover the race, too. I linger too long in Bilbao and get stuck behind the race, which means I am late to the foot of Los Machucos, which means I can’t drive up. Is it possible to ride up Los Machucos on a folding bike, even a carbon fibre one with eleven gears? There is an evacuation road, which the riders will come down after the stage. Trouble is, it is as spectacular/silly as the other road, which the race is taking.

There’s nothing for it but to commit to the task, pedalling up those slabs of slatted concrete. Riders like to say that they take a Grand Tour ‘one day at a time’ and my approach to this climb is similar, but more microscopic, in that I’m taking it ‘one rev at a time’. I can’t think beyond the current, very slow pedal revolution.

After a kilometre or so I see a slate grey campervan parked up ahead of me. As I get closer, I see that it has subtle, discreet décals. It’s the Roglič mobile: home to Primož Roglič’s wife and three-month-old baby as they follow the race. I have no idea why it is parked here, in the middle of nowhere. Eventually I draw level and by the doorway see a pair of flipflops: Mrs Roglič and Baby Roglič must be inside. (When I mention the campervan on the podcast one listener suggests that in addition to Superman and Nairoman we should introduce a new nickname for Roglič: Camperman.)

About 40 minutes in to my ride, as I wobble on up holding my phone on the handlebars, watching the stage on the Eurosport Player (excellent 4G up here), I realise I am not going to make it. I have ridden five kilometres but there are still two kilometres to the top. On the screen, Pogacar and Roglič are three-and-a-half kilometres from the summit. Do the math.

I am back down the hill in what feels like two minutes, in plenty of time to intercept the riders as they arrive at their buses.

I sleep well.

The Grand Tour Diaries is available from thecyclingpodcast.com/book. Take a closer look at the ATTO here.